The liberal command to “celebrate diversity” misses that there is often little to celebrate. It takes a truly privileged and cosseted mind to imagine that identities are always a joyful embrace of essential natures. Minorities can be manufactured by the prejudiced and powerful who need outsiders for their supporters to define themselves against. If the prejudice and power did not exist, nor would they.

Brexit Britain may not be up to much but it has become a world leader in creating identities no one needed or wanted. You would have been met with incomprehension in 2015 if you had declared yourself a “Leaver” or “Remainer” or talked about European Union nationals in Britain and Britons in Europe as if they were aliens, who must meet the exacting demands of a suspicious bureaucracy.

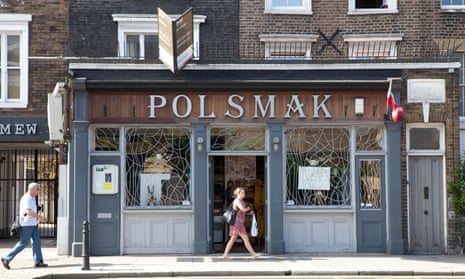

Until 2016, Europeans in Britain no more thought of themselves as members of a minority than their British counterparts on the continent did. The 3.7 million Europeans, or 5 million if you include their British spouses and children, had lived, loved and worked in Britain for decades in many cases. They weren’t a minority or an identity. They just were. They’ve changed now, but not through any empowering choice on their part. Boris Johnson, Nigel Farage and Michael Gove turned their presence into a vote-winning grievance and their world fell apart.

The disorientation of Brexit has forced questions that have cut to people’s souls: what is my future, where is home? As the sports writer Philippe Auclair said: “We ask ourselves: is it possible to belong, as we desperately want to – this is our home, not a foreign posting, and most of us have nowhere else to ‘go back to’.”

The 1.3 million or so Britons living in the EU can say the same. They now hear from Britain the companion piece to the racist slogan “Why don’t you go back home?”: “You left Britain, your opinions don’t count.”

The British press once flew into tantrums when a Briton was mistreated abroad. It largely ignores them now. Remain campaigners have done their market research and pass over their plight because they know there is little public sympathy. The majority no more had the chance to vote in a referendum that directly affected their prospects than Europeans in Britain did. To top it all, they have been abandoned by nationalists who once supported them.

The argument for Brexit was accompanied by the fantasy that Britain could compensate for the loss of access to its largest market by joining the reassuringly white and English-speaking “Anglosphere” of Australia, Canada, the US and New Zealand. This is why they talk of an “Australian-style points system” and “Canada-style trade deals” and hope against all evidence that the protectionist Donald Trump will rescue Britain.

Brexit has shown that you have to be the right type of Anglo to be admitted to the Anglosphere, and Anglos in Europe need not apply. They are stereotyped as pensioners on the Costa del Sol, when 80% are of working age, transformed into citizens of nowhere, flitting between the banks of Frankfurt and Paris.

I will spare you the gags about the hypocrisy of rightwing movements, which emit gammony belches about the absurdities of identity politics while creating a nationalist identity politics of their own. The gags write themselves and, in any case, aren’t funny. Better to understand the connections between the minorities and the majority and realise that what happens to them could happen to you.

Migrants in Europe and Britain feel a sense of betrayal that ought to be familiar. They have lost a certain idea of Britain as a moderate, tolerant country that did not allow political fakes and flakes to lead it off on mad ideological projects, a sentiment you may share.

From 2016, they’ve been told not to worry because “it’ll be fine”. As events have turned out, Europeans must apply for settled status in Britain and place their lives in the hands of the Home Office, one of the worst-run departments in Whitehall. Imagine that the Home Office has a 90% success rate in tracking down all who are legally entitled to stay – no one believes it will, but imagine. There will still be 320,000 Europeans waiting to be caught in the next Windrush scandal. Boris Johnson said that Europeans could have “absolute certainty” he would honour Vote Leave’s promises to protect them. Already his government is denying full rights to 42% of applicants.

British people in Europe, meanwhile, have no certainty about whether they will have freedom of movement within the EU or the right to return to Britain with their families. Nothing has been settled. Nothing is fine for them or the rest of us.

Ireland barely featured in the referendum campaign. The failure of Westminster politics and journalism to face the border question was not accidental. Vote Leave’s Theresa Villiers led a propaganda campaign that assured voters that concerns over border controls in Ireland were “scaremongering”. It’ll be fine.

Were you worried about how we leave the EU without hurting the economy? You should not have been. Supporters of Brexit swore the task of striking a free-trade agreement with the EU should be “one of the easiest in human history”. It would be fine. We were told ad nauseam that EU rights for workers and environmental protections would stay in place. They would be fine. Now Johnson’s government says destroying them is “vital for giving us the freedom and flexibility to strike new trade deals and become more competitive”.

For years, I’ve believed it is worth watching how a state treats foreigners under its control because you see how it will treat the rest of the population if it has the chance. As rights go, horizons narrow and the culture turns rancid, the identity politics that Brexit Britain is forcing on Europeans is becoming the politics it will force on everyone else.