- India

- International

Can’t run world’s fastest growing economy on employment support…Must create employment: PMEAC member Rathin Roy

Dr Rathin Roy, member of PM’s Economic Advisory Council, blames ‘structural problems’ lasting years for plateauing domestic consumption, believes smart policy and not expensive schemes will help meet targets, and explains why he thinks railways and smaller cities are collapsing

Dr Rathin Roy with Special Correspondant Aanchal Magazine in The Indian Express newsroom. (Express photo by Amit Mehra)f

Dr Rathin Roy with Special Correspondant Aanchal Magazine in The Indian Express newsroom. (Express photo by Amit Mehra)f

In March this year, Dr Rathin Roy, member of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council (PMEAC), sparked a debate when he said that the Indian economy was facing a “structural slowdown”, and could slip into a “middle-income” trap. His comments came in the backdrop of the Ministry of Finance’s Monthly Economic Report of March 2019 that warned of “slight” economic slowdown in 2018-19. The director of the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, an autonomous research institution under the Finance Ministry, argues that the demand generated by the top 100 million, which has been driving India’s growth so far, has started to plateau.

AANCHAL MAGAZINE: You have said that India is headed towards a middle-income trap. Can you elaborate?

When you look at what Bombay (Mumbai) likes to look at as its indicators, these are diagnosing a far deeper structural problem in the economy. It has nothing to do with the last five or 10 years, but it has everything to do with what has been the engine of growth since 1991. The leading indicators for Bombay are automobile, two-wheelers, air conditioners, refrigerator sales… What do all Indians consume? There are five things — food, clothing, one house minimum in our lifetime, healthcare and education. If that is so, how come these are not indicators in Bombay?

Since 1991, there has been a conscious attempt to ensure that the principal engine of growth is the consumption by the top 100-120 million (people)… When I was a kid in 1988, everything in my life was rationed. My food, drinks, railway and air tickets, car, were rationed. Today we have no rationing. Now take an individual earning minimum wage in 1988. Has the price of food, clothing, shelter, health and education moved in such a way that this individual has a better life today? The answer would be not so good. This means that person has not contributed to growth the way we did. But that’s fine and India is a big country. And people like us are 100-120 million. That is the size of the German market. So in terms of a market, we must be very happy. But when you all have bought your cars and houses, what will you consume next? You will want to go for holidays abroad, have your healthcare done in Singapore, you will want your children to study abroad, and that is what is happening now. This additional discretionary demand this 100 million is generating is increasingly moving to things that India doesn’t produce… If you look at the import bills for foreign holidays and education, it is going up by hundreds of percent a year for the last six-seven years. So domestic consumption is plateauing for a structural reason. And here if you tinker and say add fiscal policy, it is like I have a fracture and you are giving me a massage. That game is over.

SANDEEP SINGH: This is where the debate over jobs comes in. We have not been able to create jobs.

You can’t create jobs. Activities create jobs. The question is, will the activities used for the consumption of the top 100 million create more jobs? No. Therefore, what we need to have now are policy measures that go beyond government. We have to ask the tough question — how come we are not able to meet the demand for more food, clothing, housing, health, education, at affordable prices? The key point here is this: You can subsidise for 90 per cent of the population, but somebody earning the minimum wage or above should be able to afford those five things without subsidy. The structural problem is that they cannot.

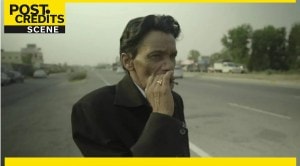

Rathin Roy: Why do farmers commit suicide? It’s lack of control over the business. Nobody has asked what is the unsubsidised rate… We have producer, transit, and consumer subsidies. The business model is destroyed

Rathin Roy: Why do farmers commit suicide? It’s lack of control over the business. Nobody has asked what is the unsubsidised rate… We have producer, transit, and consumer subsidies. The business model is destroyed

Also, the solutions to this are very different. Let me start with agriculture. The objective function of Indian agriculture has been to grow more food. We have subsidised and cross-subsidised that sector to such an extent that today as an economist I find it impossible to calculate the non-subsidised cost of a nutritional meal at any location in India. What kind of business model does that give a farmer? Why do farmers commit suicide? A farmer commits suicide because of the lack of control over the business process. Nobody has asked what is the unsubsidised rate in an agricultural business where the farmer will earn a 15 per cent rate of return. We have producer subsidies, transit subsidies and consumer subsidies. The business model has been destroyed. That is why you are not getting ‘activities’ in the agriculture sector that are profitable, and thereby create purchasing power. Then you say okay, if agriculture is able to work at 15 per cent, then there is oversupply of labour, then that labour needs to participate in non-farm activities, then the income earned will enable those families and communities to migrate to a city… Not like today as a supplicate, as somebody who is treated with no dignity in Gurgaon, in Bombay etc.

In the other scenario, people coming in from UP, Bihar (to cities) will be migrants with capabilities to search for jobs. That will transform the quality of jobs that one gets… Policy should focus on setting up manufacturing capacity where the majority of the country lives, instead of condemning them to a permanent journey to Dubai, Bombay, Bengaluru, Gurgaon, Noida or Chennai, and then feeling good about the fact that they are getting jobs there as watchmen, waiters and drivers.

“There is no reason to doubt the intrinsic credibility of the GDP, or other statistics… As for how the government could have dealt with this better… It would have been well advised to have professionals comment on these,” says Rathin Roy.

“There is no reason to doubt the intrinsic credibility of the GDP, or other statistics… As for how the government could have dealt with this better… It would have been well advised to have professionals comment on these,” says Rathin Roy.

Also, we have to produce (things) which all Indians consume, and that which all Indians want to consume. That you have to subsidise to help somebody purchase the five basic things is absurd. Something is wrong with that model. You have to recognise and change that.

HARISH DAMODARAN: But if you look at the rural wage growth, it has been in double digits. So incomes have definitely been growing. The structural problem seems to be of the last five years, because of demonetisation, the Goods and Services Tax etc.

I disagree. There has been only one three-year period between 2005 and 2008, and I may be wrong on the years, when the consumption of the bottom 20 per cent grew faster than that of the top 20 per cent. So it’s not about the last five years. Before the last five years, the last mile was helping, and there was a period when agricultural wages grew. But I’m afraid these grew because of the subsidy called MGNREGA. It was not a bad subsidy because it forced the rural living wages to go up by creating demand. But, you cannot run the fastest growing economy in the world and then provide an employment support programme. The fastest growing economy has to create employment on the strength of its own performance. The boost was temporary, as will happen with every fiscal stimulus you give, every welfare and compensatory handout you give.

ANIL SASI: One of the trends that we have seen in the last five years is the repeated fallback on tariff hikes to protect the domestic industry. There are a number of sectors, such as telecom, where duties have been hiked primarily to address grievances of the domestic industry, mostly seen as protectionism. Isn’t that essentially pushing us further down the road, the road you mentioned we should avoid to get out of this middle income trap?

Tariffs can do two things. They definitely make life more expensive for people or they make people not consume what they were consuming before… If there is a 2,000 per cent tax on air travel, a lot of us will stop flying. You will have to go back to the railways. Then, you will get mad at the services — delays, food etc. Then we will start investing in the improvement of the railways. That’s one good way to go.

Now, if your tariffs are involved in industries, where the demand is inelastic, then you will not consume less but you will pay higher prices. If I’m able to produce a mobile phone at eight, and the tariff means that I will sell the mobile phone at 10… so prices will go up for the consumer… That cost benefit calculation has to be done commodity by commodity and it is hard work. Australia has the Australian Productivity Commission. It’s a constitutional body and it estimates your productivity and the elasticity of demand and supply for every commodity in Australia. That information is presented to the parliament, and on that basis, economic policy decisions are taken. But we don’t do this hard work. Somebody imposes the tariff, somebody does something else. In that sense, I’m against it (tariff)… If you are able to justify in public why you are doing the tariff and what the consequences will be — which is never done — then I am for it, although I may disagree with the principle. But that is not done, so I don’t like it.

LIZ MATHEW: Do you think the schemes implemented by the government to yield growth, like the skill development scheme, did not meet their target?

This again is a problem. It’s very interesting that the discourse that we have in this country is about schemes and targets. It happened in Communist countries, right? When the Prime Minister said that he wants to double farmers’ incomes by X, he was actually making a paradigm shift. I think that paradigm shift was bipartisan… The objective of agriculture is to make sure it is a viable business model. That’s a paradigm shift. There is no scheme there. There is an attempt to reassess the kind of interventions we make in agriculture with these objective functions in mind.

The second is low-cost housing. The idea that we should provide housing at affordable prices to people earning the minimum wage and above, and do it in an un-rationed fashion, is now part of the mission of the government… But that is not what people focus on anymore. In contrast, we are using the word ‘scheme’ everywhere. We are not adopting the economic logic and analytical hard work required to make our big policy proposals succeed.

I shuddered when I saw that the entire schemes initiative has been reduced to creating a new ministry. For me that is the kiss of death. If we say India needs skills, set up a skills ministry, then the whole thing collapses into what I call proto-Communism, where you are setting up institutions and hiring people. It doesn’t work that way.

We are a two trillion dollar economy and such crude approaches will not work. We will need to do the hard work of pin-pointing what exactly is it that we want to do. It’s not about spending money, it’s about doing things smartly and changing policies. It’s not expensive; schemes are expensive.

SUNNY VERMA: The Economic Advisory Council to the PM was constituted after a sharp slowdown in the economy. Has the council been able to advise the PM on economic issues or did it take a back seat because of the politics, elections etc?

That would be best answered by the Chairman (PMEAC).

ANIL SASI: But has the government been receptive to the PMEAC’s suggestions?

I am resisting saying this… There is no cause or effect between the two. Some of the initiatives that were taken are consistent with some of the ideas (of the PMEAC). The doubling of farmers’ income and affordable housing for all… These are the levels at which this happens. Say, there is a person living in one of the poorest districts in India. If I impose tariffs, or I don’t, will it make any difference to that guy? If yes, then should I get out of the business of tariff making? So that kind of medium-term thing you cannot ask in the short term. In the medium term, you can do it because you have the equipment, and you have the desire and the political ambition to transcend present-day constraints and work towards that situation… This I think all sides of the political house lack. There are no social movements to push us towards this medium-term objective, and so it will have to come from political statesmanship… By nature bureaucratic and technical people like me, our bread and butter is talking about the long term. If I have to sell my services as an economist, my best bet is to predict the interest rate in October. My best bet is not to talk about the person in the poorest district and how policy will change his life. And that’s what people pay you for, for the short term. Dhandha short term main chalta hai (Our work is for the short term). But politics, development, and economy should be for medium term.

P VAIDYANATHAN IYER: Your observations about the structural weaknesses of the economy show that on the one hand we are not able to provide services — which are being imported — for the rich, and on the other we are not creating affordable services for the poor either.

That is not how I will describe it. First of all I am not speaking of the poor. I am speaking of the non-poor who is not rich. In India, the economics is not difficult, but the whole political sociology is what imposes major economic constraints. A consequence of this is the unevenness of opportunity and participation in delivering growth. I will give three examples — railways, higher education and urban services. When the elite abandoned the railways, the railways collapsed in terms of service and quality. Same for higher education. For example, many of you must be migrants to Delhi. You were not born here. In the older days, if you finished your career in Delhi, it didn’t mean that you would retire in Delhi. You would retire in Bhubaneswar, Sambhalpur etc. The advantage was that when someone like you went back, and something in the urban services didn’t work, you called up the district magistrate and they would take notice. Those communities would be built. But the community relations break when there is unequal growth. It has broken in the railways, higher education etc. How many of you are going back to the small town you were born in? And why would you go back? The quality of life and income are so much better here. There’s a consequence of that for every small town, for every train, for every higher education institution in the country. So it is not the rich-poor divide, it’s about those who benefited and those who didn’t. What decision did the beneficiaries take and the consequences for those who were left behind… that is the challenge we are facing.

AANCHAL MAGAZINE: You mentioned structural issues, markets not leading to perfect outcomes, uneven distribution etc. In such a situation, if the government has to spend to spur growth, how does it then achieve its fiscal targets?

If you have a structural problem, the solution is not spending money. It is to increase productivity, make government interventions more effective… If you wish to improve the quality of agricultural extensions in India, then you don’t have to spend as much money as two airports. I am pleased that the government is fiscally restrained. The job of the government is to make smart policy interventions and not spend money. I am here talking primarily about the Central government, but it’s also for state governments. Also, the responsibility of addressing this constraint cannot be put on the government alone. Private sector and society will both have to change. We need a national conversation.

BANIKINKAR PATTANAYAK: There have been questions over the new methodology of GDP calculation. Where did the government go wrong?

I don’t have a clue. I am not a statistician. As an economist I know that all numbers are estimates. Now which estimate is good or bad, ask a statistician. But as for how the government could have dealt with this better… It would have been well advised to have professionals comment on these matters, whether positively or adversely, and then foster a conclusion, through professionals, statisticians and consumers of data who were found credible. The business of civil service (officers) and others making these pronouncements is an unfortunate one. It’s got nothing to do with a political party, it has been happening for over 20 years. It is wrong because the Indian statistical system is a credible one. The tax numbers that we put out may be volatile but they are credible.

It could have been far better managed, yes, but there is no reason to doubt the intrinsic credibility of the GDP, or other statistics. There is good cause for competent people to lock themselves up in a room and argue the matter out, as was the case before Facebook and Twitter. That luxury has been taken away and we need to take it back. Doing your research, keeping your mouth shut… It may take a few months but will be beneficial in the long run.

Buzzing Now

Apr 18: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05